By Nina Amelung

Back in 2015, after the “long summer of migration” (Kasparek and Speer, 2015), I had volunteered in one of the emergency shelters (Notunterkunft) in Berlin-Kreuzberg that were rapidly installed in very improvised conditions. By then refugees’ reception was highly chaotic. Berlin’s municipal government failed to provide adequate solutions. Its understaffed administration was absolutely overwhelmed after Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to suspend the rule of the Dublin Regulation. This led to dramatic consequences, so that refugees were left to sleep on the street outside the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales (Lageso), Berlin’s administrative agency responsible at the time, and in other improvised accommodation (Auslender 2023, 306).

I came regularly to the school gym at Wrangelstraße where refugees, mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, were accommodated, under provisional and precarious circumstances. I played with kids, listened to stories of young men, some of them minors. I learnt about the situations in their home countries that had motivated them to flee and the often traumatizing experiences of how they had made their way to Berlin and how they were longing to find some rest and peace, impossible in their present accommodation. These experiences left a deep impression on me. Civil society organizations and volunteers played a substantial role in trying to fill the gap that the asylum governance collapse had created (Auslender 2023, 306). And it all felt like a drop in the ocean when a competent, safe and integrating reception and processes to facilitate access to safe housing were needed.

After I had witnessed this precarious accommodation in 2015, I knew lots had changed, and I was curious to learn accommodation and housing for forced migrants had developed and eventually partially improved. I was particularly interested to understand the challenges that vulnerable groups of forced migrants continue to face in accessing housing and assistance, and how the role of civil society actors in assisting access to housing had evolved, but also if migrant- and civil-society-led “good practice” initiatives had grown over time.

In two visits, the first one in November – December 2024, the second one in March 2025, I had a chance to do so thanks to the DASH secondment mechanism and the invitation by the association Inwole e.V. (https://www.inwole.de/english), a partner in the DASH consortium located in Potsdam, Germany. The fruitful and supportive collaboration with Hanna Blank from Inwole e.V. enabled me to explore further the housing situations of forced migrants in Potsdam and Berlin. I had conversations with several migrants who told me about their struggles and solutions to find access to housing, and visited different initiatives of civic actors to support migrants in getting access to housing. I saw a reception center and temporary accommodation for forced migrants, and learnt about collaborative and inclusive approaches to housing for migrants. Last but not least, I read websites, policy documents, news articles and scholarly literature on migrants’ housing situation and integration in Berlin and Potsdam.

Inwole e.V. provides a space for the respectful assistance of migrants

I began my stay by learning in conversations with Hanna Blank about Inwole e.V.’s diverse and longstanding engagement with migrants and the support they give them to access to housing and assistance.

Inwole e.V. has a long history of supporting migrants’ self-organization with activities that aim at their empowerment, focussing on migrants’ needs and building their capacity. Among the more prominent initiatives was one in which they worked with male migrants from different African countries to strengthen their abilities to enter the labour market while they waited for the regularization of their residence status. Inwole e.V. has also given priority in their projects to skills training for women to enable them to enter male dominated professions (such as carpentry or blacksmithing).

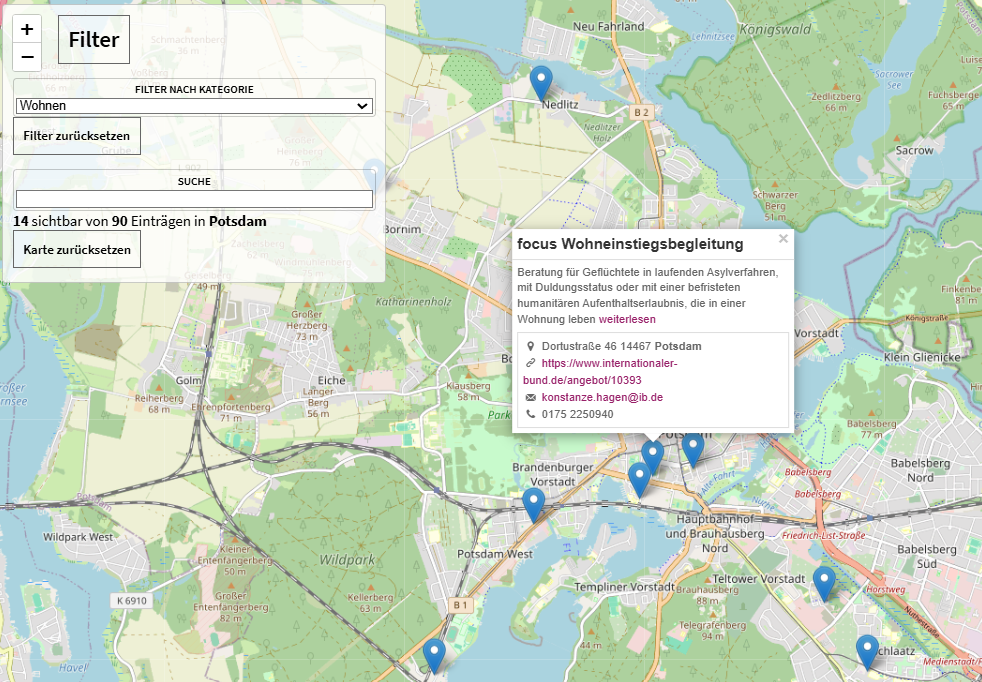

With regards to housing, Inwole e.V.’s project called “Women to Women” stands out as an empowering and creative initiative that takes housing as one of many integral aspects necessary to begin a new life and build a new home. Financed by Brandenburg State’s Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (2021 – 2022), it offered girls and women with migratory experiences technical training to work with text, photography, video and podcasts to produce an internet platform (https://www.womentowomen.de/) that relates their experiences and dreams in Potsdam in a way that is also instructive for others. Their stories document their challenges and learnings in the city where they arrived after experiencing forced migration. One outcome of this project was the creation of an interactive map of locations in Potsdam that provide orientation for girls and women with migratory experiences. Besides locations that are relevant for issues related to health, education, and work, among others, the map includes locations related to access to housing, such as housing advice services, as well as shared accommodation for asylum seekers, refugees and migrants, including specifically for migrant women and children.

I also had the opportunity to participate in Inwole eV’s ongoing activities with migrant women, which straightaway put global migration politics on the table in Inwole eV’s meeting room. I thus got a chance to learn about the views of those who are ultimately affected. On December 10 2024, two days after the Assad regime collapsed in Syria during a major offensive by opposition forces, we sat with L. and N., two women from Syria, together with Hanna and her colleague from Inwole e.V. in Potsdam for a language café for women that they organize regularly. The language café brings people together to spend some time learning the German language, but also creates a sense of community and support for all ongoing matters that may require assistance. Surrounded by Christmas decorations, and with a hot coffee cup in our hands to warm ourselves up against the winterly cold outside, the main topic L. and N. want to talk about is Syria. And how they feel about the still unclear situation and the possible futures of their country. These days, when news outlets lead with headlines about the German political discourse, and move quickly to consider the possibility of returning Syrian refugees back to their home country, I listen to L. and N. and their views on the situation. At first, they were both relieved and joyful. But hearing the experiences of their close relatives and friends back in Syria, they are now concerned, uncertain and scared of what will be happening. Despite this, again and again, their laughter fills the room. They don’t want to return. Their lives have been here now for years, they are integrated, they have found a home here, and want to stay. Despite being in a country which gives women with a headscarf a hard time finding a job or a flat; despite being in a country whose people smile and laugh too little, they say. They are here to stay.

Picture 4 and 5: Inwole e.V.’s language café with Syrian women, credits: Nina Amelung.

Taking the collaboration with Hanna Blank and Inwole e.V. as a starting point, I got in touch with another inspiring Syrian woman, Manal. I met Manal for lunch in Potsdam and she generously told me about her life in Germany. She found a flat in a neighbourhood in Potsdam she enjoys living in. She tells me about the friendly neighbourhood she has and about the good relations she established and maintains with her neighbours. She tells me about the importance of finding good housing to finally beginning a dignified life. Manal volunteers and is actively involved in various activities. Later on, she invited me to the Arbeiterwohlfahrt (AWO), a voluntary welfare association in Potsdam, to attend a language café to talk about democracy and Syrian migrants’ political participation in Germany, which she co-organized. The conversations with L., N. and Manal leave me with the impression of rather well-integrated women who over time have established their lives and found their new home in Germany.

While L., N. and Manal have mostly found their way to dignified living conditions, many others have not (yet).

The long and difficult path to permanent safe housing

The usual path to housing for forced migrants begins with an initial reception center; various forms of additional temporary housing can follow afterwards. Ukrainian refugees are an exception as the Temporary Protection Directive gives them easier access to housing. But the path to access permanent housing for forced migrants, even when they can access social support, continues to be extremely difficult as rental markets are under high pressure, leading to high prices, low availability, and inadequate distribution (Lakševics et al. 2023: 83).

From news articles and literature reviews, I had learnt that the initial governance collapse in 2015 and 2016 mentioned earlier was followed by the introduction of New Public Management (NPM)- centred policy governance in the area of refugee integration and housing policies, which prefers market-oriented policy solutions rather than centralised administration (Auslender 2023). This has led to what Bernt et al. 2022 have called “internal migration industries” at the local level. Renting out public housing stock to disadvantaged people, with migrants a particular target, has become a new business opportunity to create profit. Private service providers have a key role in controlling access to housing (Bernt et al. 2022, Kreichauf 2023).

I wanted to get a better understanding of the conditions in temporary accommodation run by private companies or civic entities and explore migrants’ lived experiences in different temporary situations and settings. So I visited the Tempelhof mass accommodation , which demonstrates the constant precarious conditions experienced in temporary housing solutions. Immediately after the long summer of migration, Tempelhof airport – located centrally in the city and used as a museum before – was turned into a reception center for asylum claims processing. It was run by a private company that received many objections from other refugee-supporting organizations for not providing adequate housing conditions. It used quick-build modular container housing (modulare Notunterkünfte) places in the airport hangars. Initially in October 2015, 2,500 migrants were housed there. Refugees were packed tightly, with 12 people living in every 25 square metres without privacy (Auslender 2023, 312). Although the registration process was supposed to take a few days, allowing refugees then to move on to better accommodation, many lived in the hangar for weeks or months (ibid, 313). It closed by the end of 2016 when inhabitants had been moved step by step to other accommodation.

From 2022, Berlin has used two former airports, Tempelhof and Tegel, as mass refugee reception centers, mostly for incoming refugees from Ukraine. After Tempelhof was put into operation again, it soon became Berlin’s biggest reception center, accommodating up to 1,600 people. Then the airport Tegel in the north of Berlin was also opened as refugee accommodation. The Tegel accommodation grew quickly to a massive scale and is now the biggest refugee accommodation in Europe, housing approximately 5,000 people. Tempelhof and Tegel are meant to be temporary, but often, due to the difficult housing market, migrants stay there much longer. Tempelhof is run by the State Office for Refugee Affairs (LAF), and operated by Arbeiterwohlfahrt (AWO) Berlin-Mitte, a voluntary welfare association, and the International Bund Berlin-Brandenburg. 100 employees and a 9-person management team, together with a network of volunteers, take care of the residents’ needs and special challenges. Most of the containers are inside three of the airport hangars, while some are outside (as you can see on the pictures 5-8). All containers are furnished with double bunk beds for a maximum of four people. They are rudimentarily equipped with one small lockable locker per person as well as a table and two chairs.

A long fence separates the facilities from the wide airport field, which nowadays is used as a public park in Kreuzberg, a very central neighbourhood of Berlin. When walking by you realize that this makes the reception center quite visible to the public, and thus exposes its inhabitants and reduces their privacy.

Pictures 7-10: Tempelhof airport and container accommodation for forced migrants, credits: Nina Amelung.

Different interlocutors I met during my visit mentioned migrants’ differential treatments when it comes to housing depending on their country of origin and legal status; this also applies to temporary housing solutions. Ukrainians rarely need to stay long here, while others are waiting for a long time to move on to better accommodation. Those shared experiences I heard of mirror what has been written in the literature. Foreigners experience discrimination when trying to access the housing market in Berlin and Potsdam. Yet there is a difference between Ukrainians – often perceived as “white refugees” – who experience less discrimination in comparison with other racialized migrants (Berliner Zeitung 2022, Zeit 2022). A lot of private hosting took place when Ukrainian refugees arrived, and locals demonstrated enormous solidarity. The benefits of private hosting are that it allows migrants to access decentralised housing, as well as social exchange and integration with local residents. But it also turns out to be exhausting for hosts when migrants face lengthy procedures to move on to other accommodation (Lakševics et al. 2023: 83).

Inclusive and collaborative initiatives

I was interested in alternative housing solutions and how civic actors try to support migrants with needs, as well as inclusion- attempts to provide orientation and access to safe and better housing. So I spent an afternoon at the Café Refugio, which is part of an inclusive housing project called Refugio Berlin located in Berlin Neukölln, and learned about the concept of the “share house” (https://refugioberlin.wordpress.com/). The “share house” Refugio Berlin is in fact a shared house where refugees live together with other people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Around 40 people live there, approximately 20 of them with migratory experiences. They also work together, for instance in the café, or in different education initiatives and intercultural projects. They also offer event rooms to rent. The guiding principles are collaborative and reflexive forms of living together in solidarity, and furthering integration and intercultural exchange. It requires shared responsibility and the collective creation of a home for all. The Refugio Berlin is run by the Berliner Stadtmission. In comparison to provisional and temporary reception centers, a “share house” offers more privacy, and social integration.

When I visited Inwole e.V. for the very first time, I had already noticed that the Brandenburg refugee council (Flüchtlingsrat Brandenburg) also has its office in the Inwole e.V. building. The Brandenburg refugee council is part of a network with other civic actors called Collaboration for Refugees in Brandenburg (“Kooperation für Flüchtlinge in Brandenburg” (KFB)). The initiative works towards the improvement of accommodation and housing conditions, and specifically towards a paradigm shift away from temporary accommodation towards permanent solutions that enable forced migrants to live in their own private apartments from the very beginning. The development of long-term housing solutions for forced migrants in the arrival and settling phases is urgently needed, specifically those that tackle issues from discrimination to access and belonging (Lakševics et al. 2023).

Just a few days after my stay was over the Action Conference “Good housing for all” (Aktionskonferenz “Gutes Wohnen für Alle”) took place in Berlin, organized by Collaboration for Refugees in Brandenburg. This offered an open-space discussion forum. It brought together people threatened with homelessness, inhabitants of shared accommodation for refugees or homeless people, people engaged in housing-related activism or work, volunteers helping people find accommodation, and housing researchers and invited them to share experiences and ideas, and find ways to work together in solidarity. This appeared to be a great opportunity to collectively reflect on ways forward.

Acknowledgement: I’m grateful to Hanna Blank and Inwole e.V. for the exchange and support throughout my visits and I’m thankful to the inspiring people I was lucky to meet who told me about their own paths to finding a new life and home, and also to those who told me how they assist other people on their path. Some names and workplaces have been anonymized in this text. Further reflections will result in a joint publication project with Hannah Blank that we aim to present at the Urban Sociology Midterm Conference (RN37) of the European Sociological Association (ESA), to be held at the University of Coimbra in September 2025. Nina Amelung receives funding from the FCT grant entitled “Affected (non)publics: Social and political implications of transnational biometric databases in migration and crime control (AFFECT)”, Individual Research Grant Fellow FCT CEECIND/03611/2018/CP1541/CT0009.

References:

Auslender, E. (2023). A new direction or the same old road? Assessing refugee housing and integration policy governance in Berlin post-2016. Territory, Politics, Governance, 13(3), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2023.2222133

Bernt, M., Hamann, U., El-Kayed, N., & Keskinkilic, L. (2021). Internal migration industries: Shaping the housing options for refugees at the local level. Urban Studies, 59(11), 2217-2233. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211041242 (Original work published 2022)

Kasparek B and Speer M (2015) Of hope. Ungarn und der lange Sommer der Migration. Bordermonitoring. Available at: https://bordermonitoring.eu/ungarn/2015/09/of-hope/ (accessed 1 March 2025).

Kreichauf, R. (2023). Accommodation for profit, not for refugees: Racial capitalism and the logics of Berlin’s refugee accommodation market. Environment and Planning D, 41(3), 471-493. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758231181399 (Original work published 2023)

Lakševics, K., Franz, Y., Haase, A., Nasya, B., Patti, D., Reeger, U., Raubiško, I., Schmidt, A., & Šuvajevs, A. (2023). The permanent regime of temporary solutions: Housing of forced migrants in Europe as a policy challenge. European Urban and Regional Studies, 31(1), 81-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764231197963 (Original work published 2024)

Websites:

Aktionskonferenz “Gutes Wohnen für Alle” URL: https://www.fluechtlingsrat-brandenburg.de/save-aktionskonferenz-gutes-wohnen-fuer-alle/ accessed March 10 2025.

Berliner Zeitung (2022) – URL: https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/news/rassismus-berlin-diskriminierung-auf-dem-wohnungsmarkt-oftmals-durch-nachbarn-li.267875?utm_source=chatgpt.com accessed on 14 December 2024.

DIe Zeit (2022) URL: https://www.zeit.de/news/2022-09/16/diskriminierung-auf-dem-wohnungsmarkt-oftmals-durch-nachbarn?utm_source=chatgpt.com accessed on 14 December 2024.

“Kooperation für Flüchtlinge in Brandenburg” (KFB) URL: https://www.xn--kooperation-fr-flchtlinge-in-brandenburg-wfee.de/ accessed March 10 2025.

Inwole e.V. https://www.inwole.de/english accessed on 14 December 2024.

Inwole e.V.’s project Women to Women https://www.womentowomen.de/ accessed on 14 December 2024.

Inwole e.V.’s project Women to Women – map URL: https://www.womentowomen.de/karte/, accessed December 12 2024.

Refugio Berlin https://refugioberlin.wordpress.com/ accessed December 12 2024.