By José Antonio Ferreira

This is the image that marked my first days in the wonderfully strange, optimistically diverse, and proudly brutal(ist) city of Belgrade and it stayed with me. A sadness which, I am certain, will not fade—because a beautiful part of history is gone. The Hotel Jugoslavija.

While travelling on public transport towards Zemun last December, passing behind that same site, the melancholy returned in all its full splendour. ‘Life flows. Symbols remain.’ Embarrassed by the use of Serbian, they underlined it in a kind of Esperanto-English: ‘Danube Riverside’ – https://danuberiverside.rs/. Where have I seen this before?

That initial sadness, I came to understand, was not the sentimental melancholy of a tourist fascinated by socialist iconography (only the iconography). It exposed human greed in one of its starkest forms. And greed, as we know, has no homeland. A magnificent building being destroyed (“the symbol remains”?) to build a nondescript building like so many others in our cities, as in the city of Porto. This “normalisation”, this “flow of life”, seems to be devouring us. The construction of anonymous buildings replacing ones that were proudly assertive and stood for an idea of society — for better or for worse. I like to think that it was for the better as I gaze upon old New Belgrade. Today, buildings in nearly every city only represent money. A lot of money.

You should notice this subtlety (or rather, the lack thereof): these buildings, identical to so many others across different cities, lack the charm that repetition once had in what now feels like a distant past — like the charm you find in New Belgrade — even if nothing is being done to save them from their entrenched decay. Why did the State sell them? That question I etched into memory during a deeply enlightening Sunday walk guided by Professor Zlata Vuksanović-Macura through this area. The elegance of the masterplan, the subtlety of the buildings (despite their scale), the intentional repetition, the constructive details, and public space at the heart of a world on the brink of extinction. Belgrade Moneyfront – https://www.belgradewaterfront.com/ – teaches us the opposite. In fact, the money being spent there would be far more productively used in financing the rehabilitation of old New Belgrade. And regenerating the old Old Belgrade. But that is another utopia.

I return to that initial sadness to explain what we might have done with the Hotel Jugoslavija. Demolition was not the answer. No one in their right mind should demolish such a building. It stands there, beautiful and strong, and it could have been revived. Its transformative potential (plastic, functional, performative…) was and is evident. And it was/is environmentally healthier. And economically more sustainable — and viable, I dare say.

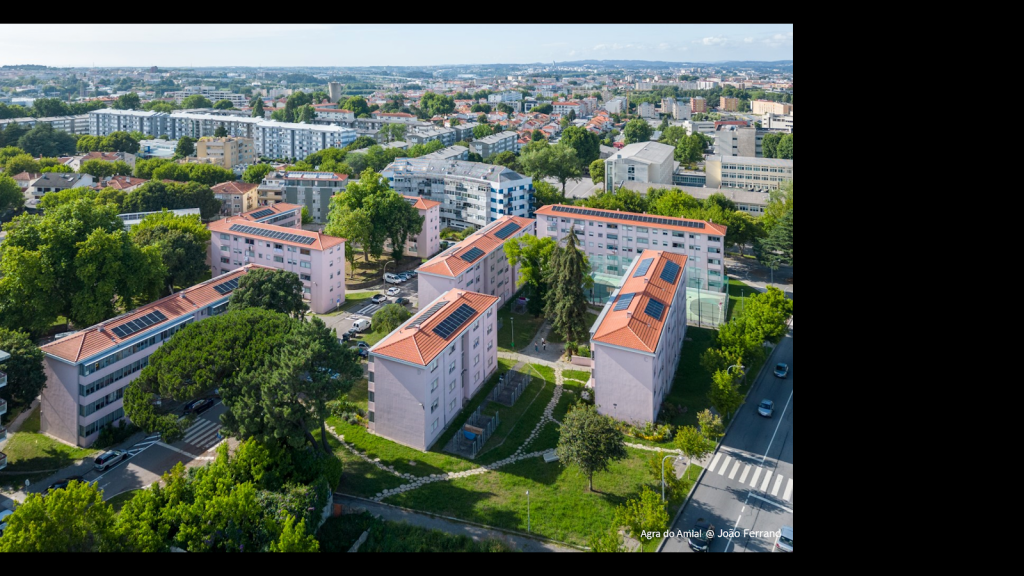

This is what we in Porto are attempting with public housing buildings that are far poorer—architecturally and construction-wise – through almost 25 years of continuous investment. First to restore the dignity of those who live there, then the dignity of the buildings themselves, and finally of the city we all belong to.

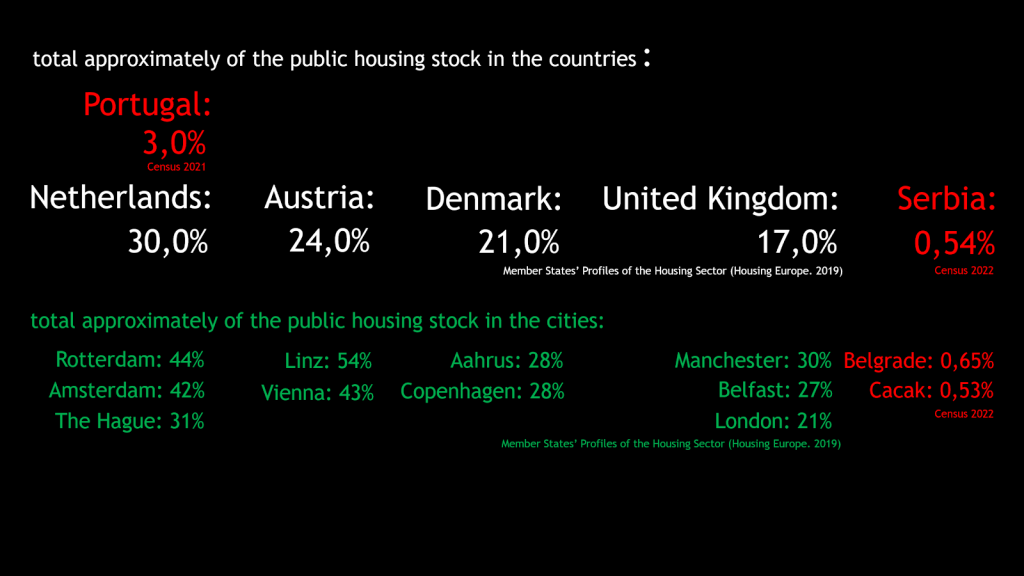

We manage 50 housing complexes, home to approximately 30,000 people living in around 13,000 dwellings under supported rent schemes, representing 12.2% of the city’s housing stock. Lisbon manages 7.7%. In Portugal, an embarrassing 2.2% is the extent of the existing public municipal housing stock. Compare this to Serbia’s 0.54%, Belgrade’s 0.65%, and Čačak’s 0.53%. In both of these countries, we are far from the figures in some of the European countries we admire and draw inspiration from. The embarrassment could hardly be greater.

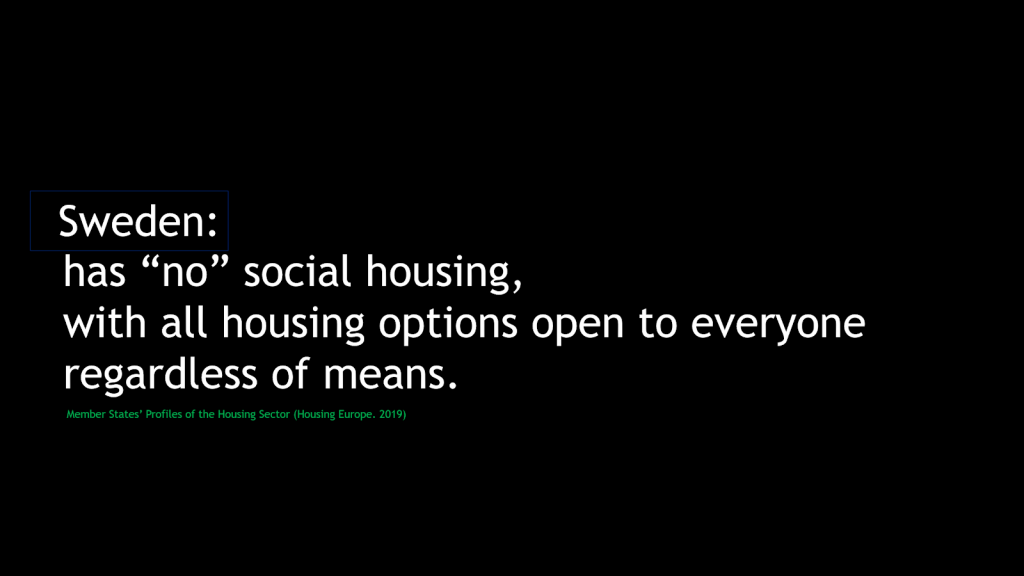

In Serbia, the proportion of public housing in the 1990s, before the privatisation of this remarkable heritage, hovered around a proud 23%. A figure that brought the country into the future. We now know that the strength of both public and private rental sectors is central to contemporary housing policy—especially that of the public sector. It helps regulate and control “market forces”. It allows for a fairer and more balanced provision of housing. It helps to promote urban quality of life, without major costs (administrative, fiscal…).

Today, the (partial or total) privatisation of public assets reveals its full effect. The ongoing cycle of poverty among most families who acquired them reveals its most harmful side. The fragile financial solvency of these families hinders the corrective and preventive maintenance of the buildings (housing complexes) and any coherent or consistent rehabilitation. And this is true in Belgrade, in Porto, and in Madrid.

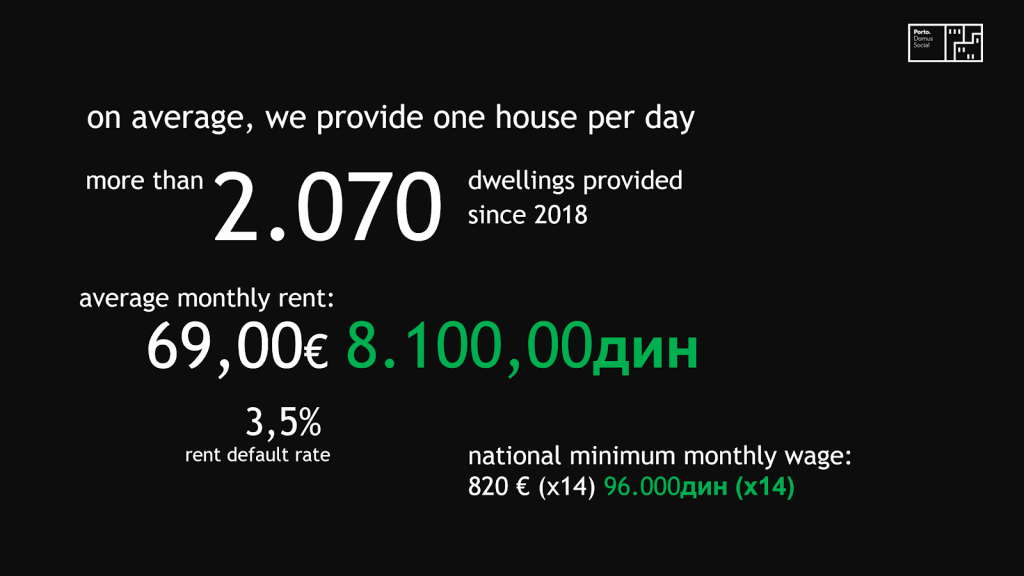

The scale of poverty among families living in Porto’s social housing is reflected in the average monthly rent: €69—calculated primarily based on household income.

These figures reveal the lack of financial means that these families – who become owners in 7 of Porto’s social housing complexes in the early 2000s – have to help support the investment needed to properly maintain the buildings. And that is exactly what is happening in thsse 7 social housing complexes today (although most of the property is still public). Degradation takes root. And the spiral of decay and obsolescence becomes much harder to reverse – a mistake that is, quite literally, costlier.

But we, too, have made mistakes. Let’s be realistic — we will keep making mistakes. That is why the sadness doesn’t fade. To fight it, I nostalgically recall May 1968 – I was three at the time – and one of its iconic slogans: “Be realistic: Demand the impossible” “Be realistic: Deliver Safe and Social Housing” is imperative.

Account of a secondment to Serbia (Belgrade, Čačak and Novi Sad) in December, based on a conversation held on 19 December 2024 at the Jovan Cvijić Geographical Institute of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Belgrade, with Serbian project partners from the Association of Urban Planners of Serbia and the Čačak Municipal Housing Agency.